Background on Tiyo Attallah Salah-El

Tiyo Attallah Salah-El playing the saxophone in high school.

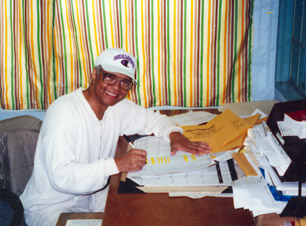

While serving a life sentence in a Pennsylvania prison, Tiyo Attallah Salah-El transformed himself into an activist, scholar, and advocate for the abolition of prisons. An accomplished jazz musician, Salah-El distinguished himself for educational and scholarly work, his musical career, his close relationship with activists and educators, and for the non-profit organization he founded, The Coalition for the Abolition of Prisons (CAP).

Born David Riley Jones on Sept. 13, 1932, in West Chester, Pennsylvania, Salah-El was the third of four children born to Riley and Ella Jones, the only black homeowners in the Red Lion district of West Chester. The Joneses were a solidly middle class family. Ella worked as a nurse, while Riley owned a successful plumbing business. Salah-El and his older siblings, Earnest and Bette, and younger sister, Hazel, all attended integrated schools. A talented athlete, playing both varsity baseball and football, Salah-El was one of only two blacks to graduate from the high school.

After graduation in 1950, Salah-El enlisted in the Army and served as a tank operator during the Korean War, earning a purple heart for wounds received in battle in 1953. After the war, he returned to West Chester to work for his father, and he began playing tenor saxophone in R&B clubs throughout southeastern Pennsylvania. After Salah-El married, he attempted for several years to juggle a musical career with his family life and work as a plumber, but the tension between his family responsibilities and the lure of clubs and women proved especially difficult to navigate. Things came to a head in 1956 when Salah-El's wife left him and took their young son to live with another man. A violent confrontation followed, and in the scuffle, Salah-El shot his wife's lover in the arm. Things deteriorated further still when the police arrived and Salah-El accidentally shot an officer in the hand.

Convicted of aggravated assault, Salah-El was sentenced to 6 to 12 years in Graterford Prison, the largest penitentiary in Pennsylvania and the successor to the infamous Cherry Hill Penitentiary. In Graterford, he continued to pursue his interest in music, learning how to read music, joining the prison band, and getting involved more generally with the community of jazz musicians there. Through Graterford, he first met Robert "Bootsie" Barnes, who was to become a lifelong friend and frequent correspondent. Practicing intensively, sitting in with the bands, and listening to the jazz show on WRTI radio, Salah-El honed his talents on the tenor saxophone.

After serving a six-year sentence, Salah-El was paroled in 1962 and returned home to work for his brother Earnest's construction company, though music was still in his blood. He began playing regularly with Len Foster's jazz band based in nearby Wilmington, Delaware, but as the band gained local recognition, he got swept up in the raucous nightlife. Similar to his experiences balancing a middle-class family life and the nightlife in the R&B circuit, Salah-El struggled to balance his love of serious music with the excitement of nightlife and women. Feeling trapped by a relationship with a pregnant girlfriend, he left Pennsylvania for Washington, D.C., at the invitation of a friend and joined the Blackman's Development Center, an African American self-help organization run by the Moorish Science Temple of America. Working as an administrative assistant, spokesman, and community organizer for the Center's drug prevention and rehabilitation program, he converted to Islam, changed his name from David Jones to Tiyo Attallah Salah-El, and became an active member of the Moorish Science Temple.

Jazz remained a constant. Through the clubs he frequented in Washington, Salah-El became acquainted with the city's underworld and got drawn into the drug culture that permeated the jazz scene. Over time, however, it became impossible to maintain this double life, engaging in drug use by night and advocating for drug prevention in the African American community by day. The physical and moral toll eventually forced Salah-El to retreat from the city and return to Media to live with his sister Bette.

Relocating to Media, though, did not resolve the underlying issues. In 1969, Salah-El and some of his friends began selling hashish and marijuana, and as their business grew, it propelled him into working for an organized crime syndicate based in Wilmington. This phase of his life came to an abrupt end in 1975 soon after his nephew, Ray Betz, approached Salah-El seeking employment and lodging. Salah-El found him work with the crime syndicate not knowing that Betz was working as an FBI informant. On July 31, 1975, Salah-El was arrested and charged with selling drugs and murder. The details of the crime are not entirely clear. Salah-El writes about the days leading up his arrest in autobiography. Discovering that he might be a target of the very organized crime syndicate in which he was employed, Salah-El decided to leave town. Checking in with his sister Bette a few days later, he learned that the police were looking for him and that a girlfriend had been found dead in her apartment. Whatever else may have happened, Salah-El was convicted of selling drugs by an all-white jury, many of whom had ties to law enforcement, and was sentenced to two years in prison.

While awaiting trial at the Delaware County Prison, Salah-El was hired to teach music to his fellow prisoners. At the same time, he happened to read about the riots at Attica State Prison and about post-Attica attempts to organize labor unions among prisoners. Inspired by the idea of prisoner rehabilitation through self-government, Salah-El began to work with civil attorney Richard Fishman to appeal to the Delaware County Prison Board and the Teamsters Local to form a prisoner's union, but his organizing efforts, exacerbated by his high pay as a music teacher, angered the guards and his cell was entered and his papers were scattered. Things went downhill from there. In 1977, the County Prison Board ruled against the union and Salah-El was convicted of murder and sentenced to life without parole. Attica, Salah-El writes, combined with the clear message sent by the Prison Board and guards that he had crossed a line, began his politicization.

After his conviction, Salah-El was transferred to the State Correctional Institute (SCI) at Dallas. By the end of 1978, he began work on a self-directed bachelor's degree in African American history through the Prisoner Education Project, hosted by Franconia College (later Beacon College) and run by Montgomery (Monty) Neill. Although Salah-El's work and materials were often destroyed by guards, he completed his degree and immediately began studying for a master's degree in political science while working as a Beacon College program advisor, helping bachelor's students determine their self-directed course of study. After he earned his master's in 1983, he was promoted to director of the Prisoner Education Project. Through his education, Salah-El gained confidence and political conviction, which aided him in taking effective legal action against the Delaware County Prison for the destruction of his materials relating to union organizing. He was awarded an out-of-court settlement.

Salah-El also began to form strong bonds with scholars and activists outside the prison. His contact with the Gay Community News, which had a prisoner pen-pal program, introduced him to gay rights activists, and he became outspoken supporter of their struggle, a truly courageous stance in the homophobic culture of prisons. His relationship with Monty Neill and Howard Zinn, who Salah-El met in 1984, guided his political development, but more importantly, these relationships formed the backbone of what became a diverse and passionate network of advocates who have provided Salah-El with essential support. Salah-El's education also stimulated his musical creativity and in the early 1980s he composed a jazz suite that was recorded live at SCI-Dallas by a group of musicians assembled by the DJ Jay Dugan.

In the late 1980s, Salah-El became familiar with the Religious Society of Friends through their work in criminal justice reform and he contacted members of the North Branch Meeting in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. After studying the Quaker religion and becoming close friends with members of the North Branch Meeting, Salah-El became a member of the Religious Society of Friends in 1993 and was granted approval by the warden to host Quaker meetings at the prison.

Salah-El's experience as a prisoner and his education and political awareness forced him to a deep reflection on the state of the prison system in the United States. Through the study of African American history and political philosophy, Salah-El determined that the foundational philosophy on which the criminal justice system is based is inherently flawed, and rather than deterring crime actually fosters a cycle of crime and incarceration. According to his analysis, the most effective recourse is the abolition of prisons. Salah-El joined an international movement calling for prison abolition and began an unprecedented mission to advocate for prison abolition from within the walls of a prison itself. To that end, Salah-El founded the Coalition for the Abolition of Prisons (CAP) in 1995. CAP grew over a number of years, and although it is no longer active, the network of scholars that made up the coalition stayed involved with Salah-El's work and the furtherance of his mission.

Salah-El continued to write and teach, and around 2008 he organized an underground pre-GED training course for prisoners, many of whom depend on passing the GED to be considered for parole. His courses grew from twenty students per year to more than 100, and many of his graduates have taken their place teaching other prisoners.

With age, Salah-El's health grew poor, and his vision worsened; he needed cataract surgery. He decided to petition for commutation and began the process of filling out the paperwork. On June 8, 2018, he passed away, still incarcerated at SCI-Dallas, at 85 years old. That October, a group of his "lifelong friends" and supporters gathered in the Du Bois Library's Du Bois Center to celebrate his life and accomplishments. Although he spent half of his life in prison, regularly battling prison bureaucracy and the indiginities of prison life, and increasingly confined to his "cage," Tiyo Attallah Salah-El showed a remarkable capacity for joy, kindness, and friendship.