Background

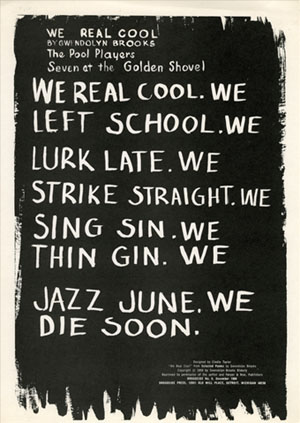

We Real Cool, Broadside no. 6

Dudley Randall was working as a librarian in Detroit in 1963 when he learned of the brutal bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. Randall's poetic response was "The Ballad of Birmingham," a work that became widely known after it was set to music by the folk singer Jerry Moore. To register his copyright, Randall printed a broadside edition of the ballad, which in September 1965 became the first publication of the Broadside Press. Over the next decade, Randall grew to become a significant poet in his own right, but as his Broadside Press grew, it too gained prominence, becoming an important venue for writers of the Black Arts Movement and the new poetic voices of Black America.

Born in Washington D.C. on January 14, 1914, the son of a Congressional Minister (Arthur George Clyde) and a teacher (Ada Viola), Randall moved with his family to Detroit in 1920. Developing an interest in poetry at a young age, Randall passed through a series of jobs and war-time military service before using the GI bill to attend college. At Wayne State University, from which he graduated in 1948, and while in library school at the University of Michigan (1951), he continued to nurture his literary talents, but it was several years more before they began to reach full flower, fertilized both by the civil rights movement and the emerging Black Arts Movement.

Although Randall wrote that the Broadside Press "did not grow from a blueprint," it grew "by hunches, intuitions, trial and error" into something more ambitious than a vehicle for Randall's own writing. While attending the first Writers' Conference at Fisk University in May 1966, Randall obtained permission from Robert Hayden, Melvin Tolson, and Margaret Walker to republish one poem each in what he called his Broadside Series, which became broadsides 3, 4, and 5 during the fall 1966. Shortly thereafter, Gwendolyn Brooks gave permission for Randall to republish one of her poems, resulting in "We Real Cool" in December 1966 (Broadside 6). Collectively, these first six broadsides, known as the Poems of the Negro Revolt, set a tone for what would follow, reflecting the culturally assertive and often radical voice of African America in the late 1960s. Intentionally simple in design, the broadsides can be viewed through the lens of a centuries-old tradition of publication. Produced and sold cheaply, typically responding directly to the social and political issues of the moment, the broadsides address subjects ranging from Malcolm X, to Stokely Carmichael and Angela Davis, Black Power, the women's movement, and revolutionary politics. Later productions in the Broadsides series are not properly broadsides at all, but simple folded sheets, resulting in four page cards, often including poems by several writers.

Following the suggestion of a reviewer in the Small Press Review, Randall took an important step forward in 1968 by issuing broadsides of previously unpublished work, beginning with Haki Madhubuti's (then Don L. Lee) "Assassination," a response to the murder of Martin Luther King. Between the mid-1960s and mid-1970s, the Press issued close to one hundred broadsides, generally one per month, featuring the works of some of the preeminent African American poets of that time. In addition to Brooks and Madhubuti, the Press published works by Alice Walker, Etheridge Knight, Audre Lorde, Amiri Baraka, Nikki Giovanni, and Sonia Sanchez.

Randall simultaneously developed the Press beyond broadsides. By 1966, he was publishing collections of poetry, beginning with his own Poem Counterpoem (written with Margaret Danner, 1966), followed by Cities Burning (on the Detroit riots; 1968), and the anthology For Malcolm: poems on the life and the death of Malcolm X (1969). Politically charged and reflecting the mood of the period, these publications enjoyed consistently strong sales. Randall also used the Press to publish works of literary criticism by Black scholars (many through his Broadside Critics Series) and works by writers from elsewhere in the African diaspora. His success as a supporter and publisher of African American poets earned him praise as the "father of the black poetry movement" and in 1985, Mayor Coleman Young named him the first poet laureate for the city of Detroit.

Randall sold the press to Hilda and Donald Vest in 1985, who continue to operate it. When Randall died in 2000, he was remembered in an obituary in the Detroit News as the city's "other Berry Gordy, the one who never left the west side of Detroit, never made millions and never became a glitter-sprinkled celebrity. Yet he, too, beamed black voices around the world."