Background on W. E. B. Du Bois

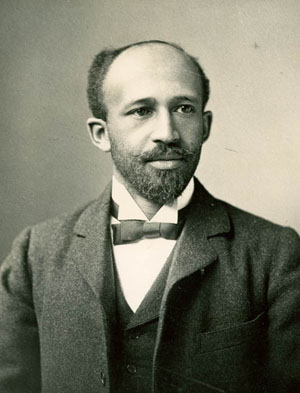

W.E.B. Du Bois, 1907

The activist, writer, and intellectual William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, was born in the rural western Massachusetts town of Great Barrington on February 23, 1868, his New England roots extending back before the Revolution and including ancestors of French, Dutch, and African American heritage. From early in life, Du Bois was recognized for his extraordinary intellectual talents. Educated in the local public schools, he graduated as valedictorian of his high school class in 1884, and with the financial assistance of friends and family, entered Fisk University as a sophomore in 1885. Thoroughly a northerner, Du Bois' experiences in Nashville were crucial in galvanizing his understanding of American race relations. To earn additional money for his education, Du Bois taught in country schools in Tennessee during the summer months, where he saw firsthand the bitter influence of segregation and the harshest expressions of American racism. The more subtle discrimination he had faced in Massachusetts coupled with this more menacing aspect encouraged Du Bois to take a more aggressive stance against social injustice.

After receiving his bachelor's degree from Fisk in 1888, Du Bois continued his studies at Harvard, enrolling as a junior and receiving his second bachelor's degree in 1890, followed by his MA in 1891 and PhD in 1895. As he had in Great Barrington and Nashville, Du Bois distinguished himself in Cambridge as a scholar. Like most Americans at the time intent upon an academic career, Du Bois enhanced his scholarly credentials by studying abroad. At the University of Berlin between 1892 and 1894, Du Bois was introduced to contemporary German social scientific theory and, more generally, he internalized the German scholarly tradition of a synthetic approach to social issues, blending history, philosophy, economics, and politics in the study of human social relations. Enamored of German culture, Du Bois also began to recognize the international dimensions of the struggle for racial justice and the connections between racial oppression and imperialist domination.

Returning from Germany, Du Bois entered an extraordinarily busy and productive period of life. In 1894, he accepted an appointment on faculty of Wilberforce University; in 1895, he completed his dissertation; and in 1896, he got married -- to Nina Gomer (d.1950), with whom he had two children, Burghardt (1898-1900) and Yolande (1901-1960) -- and published his first book, The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States, 1638-1870, the first volume published in the Harvard Historical Series (1896), was a landmark in social and historical analysis, concluding with a phrase that reflected Du Bois' growing commitment to social action:

It behooves the United States, therefore, in the interest both of scientific truth and of future social reform, carefully to study such chapters of her history as that of the suppression of the slave-trade. The most obvious question which this198 study suggests is: How far in a State can a recognized moral wrong safely be compromised? And although this chapter of history can give us no definite answer suited to the ever-varying aspects of political life, yet it would seem to warn any nation from allowing, through carelessness and moral cowardice, any social evil to grow. No persons would have seen the Civil War with more surprise and horror than the Revolutionists of 1776; yet from the small and apparently dying institution of their day arose the walled and castled Slave-Power. From this we may conclude that it behooves nations as well as men to do things at the very moment when they ought to be done.

In 1896, Du Bois also moved to an appointment as assistant instructor in sociology at the University of Pennsylvania, undertaking an intensive analysis of the African American population of Philadelphia. The resulting publication, The Philadelphia Negro (1899), is often considered his most original and compelling scholarly contribution, and it is a foundational work in the field of urban sociology. It is distinguished not only as an exhaustive study of one population, but as a sensitive portrait of a population responding actively to social stresses and to the demands of urban life, rather than seeing them either as passive victims or social cancer.

Moving next to Atlanta University to teach history and economics, from 1897 to 1910, Du Bois built a Department of Sociology with a national reputation. Perhaps the key to this reputation was the series of annual conferences Du Bois established in 1896. Each year, he and his colleagues focused on a single issue confronting African Americans, publishing the results in the Atlanta University Publications series. They planned, too, to return to each subject at regular intervals to build the basis for the longitudinal study of social problems. Although the Atlanta studies were not of uniformly high quality and were hampered by insufficient funding, taken together they offer a significant empirical basis for social analysis of the African American community at the turn of the turn of the twentieth century.

Not all of Du Bois' work was purely academic. He wrote numerous articles for the popular press and his book The Souls of Black Folk (1903) brought him national attention. In retrospect, it may be his most enduring work, having become part of the canon of African American literature. Among other things, the book spotlights the growing tensions in the African American community between the accommodationism of Booker T. Washington and Du Bois' more radical demand for full and immediate equal rights. Although Du Bois found some common ground with his rival -- precious little -- he was unrelenting in his criticism of Washington's willingness to work slowly toward equality by demanding only what whites were willing to cede. "So far as Mr. Washington apologizes for injustice, North or South," Du Bois wrote, "does not rightly value the privilege and duty of voting, belittles the emasculating effects of caste distinctions, and opposes the higher training and ambition of our brighter minds, -- so far as he, the South, or the Nation, does this, -- we must unceasingly and firmly oppose them."

Creating the institutional basis to build and sustain this agenda, Du Bois helped found the Niagara Movement in 1905. While the group never had a large membership, it did pave the way for the establishment in 1909 of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), an interracial organization based upon similar, though somewhat less radical principles.

With activism consuming much of his energy, Du Bois left Atlanta University in 1910 to become director of research and publicity for the NAACP. A natural writer with previous experience editing The Moon (1906) and Horizon (1907-10), Du Bois was also appointed editor of the monthly journal of the NAACP, The Crisis. His numerous articles and editorials in Crisis solidified his position as a major spokesman for African American rights.

Freed of his purely academic commitments, he also continued to write for the popular press, publishing a number of highly regarded books, including The Negro (1915), Darkwater (1920), The Gift of Black Folk (1924), and the novels The Quest of the Silver Fleece (1911) and Dark Princess (1928). Among his most ambitious projects was a pageant of Black history and Black consciousness, The Star of Ethiopia, written both to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation and to provide a counterweight to the racist Hollywood cinematic epic, Birth of a Nation. A poet, novelist, and playwright himself, Du Bois had a deep interest in African American literature, from folk music to the writing of the Harlem Renaissance. Du Bois even helped established a theatre troupe in 1924, the Krigwa Players, in which "Negro actors before Negro audiences interpret Negro life as depicted by Negro artists."

During the first three decades of the twentieth century, one can discern two general trends in Du Bois's thought. First, he began increasingly to extend his analysis of the color bar beyond the borders of the United States to the world scene. A vice-president of the first Pan-African Conference in 1900, Du Bois helped organize a series of Pan-African Congresses between 1919 and 1927 that recognized the solidarities of people of color around the world and the need to combat racial oppression and imperial domination of underdeveloped countries.

Secondly, while the NAACP and Du Bois both insisted upon the full integration of Blacks into the mainstream of American life, the onset of the Great Depression in 1929 and the intransigence of whites on racial matters gradually led him toward a Black nationalist solution of the race problem, stressing Black control of businesses, cooperatives, and other similar institutions as the key to Black survival. In this position, Du Bois began to depart from the mainstream of the leadership within the NAACP, resulting in Du Bois' resignation from the organization in 1934 and his departure from the editorship of Crisis.

Returning to Atlanta University, Du Bois resumed teaching duties and the scholarly life. His Black Reconstruction (1935) ran directly counter to the predominantly white historiography of the Reconstruction period by emphasizing the contributions of African Americans in the South during the years immediately after the Civil War. Although the book was criticized by Marxists and Non-Marxists alike, its basic interpretation was to become widely accepted by historians. He also wrote Black Folk, Then and Now (1939) and Dusk of Dawn (1940), and in 1940, he founded Phylon, a quarterly social science journal. With support from the Phelps-Stokes Fund, he also became involved in the preparation of an Encyclopedia of the Negro, a work that saw only a preparatory volume published.

Still remarkably active and productive in his seventies, Du Bois retired from Atlanta University in 1944. He soon returned to the NAACP, where his duties revolved around special research projects, especially relating to the place of the African colonies in the postwar world, and where he served as consultant for the NAACP to the United States delegation at the founding meeting of the United Nations. The old rifts, however, were not so easily healed. In 1948 Du Bois was dismissed after continuing disagreements with other officials over NAACP policies.

In his later years, Du Bois served as a co-chair of the Council on African Affairs and chair of the Peace Information Center and the American Peace Crusade. In 1950, he made his first and only foray into formal politics, running for the U.S. Senate from New York on the American Labor Party ticket. Ironically, perhaps, this brush with formal politics was paired with a less congenial one. During the anti-Communist hysteria of 1951, Du Bois's activities on behalf of the Peace Information Center led to an indictment against him and four associates as unregistered foreign agents. Although the charges were dismissed as groundless later that year, the attack by an arm of his own government was a bitter experience. Du Bois nevertheless continued his work in peace and international affairs, visiting Russia and China.

Du Bois became a member of the Communist Party of the United States in 1961. That same year, at the age of ninety-three, he moved to Ghana at the invitation of President Kwame Nkrumah to serve as editor of an Encyclopedia Africana. Although poor health limited his work, Du Bois continued to study and write. He took Ghanaian citizenship and on August 27, 1963, died in Accra at the age of ninety-five. Du Bois was survived by his second wife, the writer Shirley Graham Du Bois, whom he had married in 1951.

Over his lifetime Du Bois wrote or edited more than three dozen books and hundreds of articles. His accomplishments were many. As an activist and organizer, Du Bois helped usher in the modern civil rights movement by founding and building the Niagara Movement and NAACP, and he helped create periodicals that became important voices for Black identity. As a scholar and founder of American sociology, he contributed early and important works in the literature of demography, race sociology and research methodology, he helped define the continuous social survey and the fields of social stratification and race relations. As a writer, his work earned him election to the National Institute of Arts and Letters. Although Du Bois's reputation suffered among white Americans during the McCarthy era, and although he died in 1963 before the reputations of McCarthy victims were rehabilitated, his impact and influence were international in scope. A generation after his death, Du Bois remains a potent figure internationally, and a source of inspiration for millions.