Background on David Levering Lewis

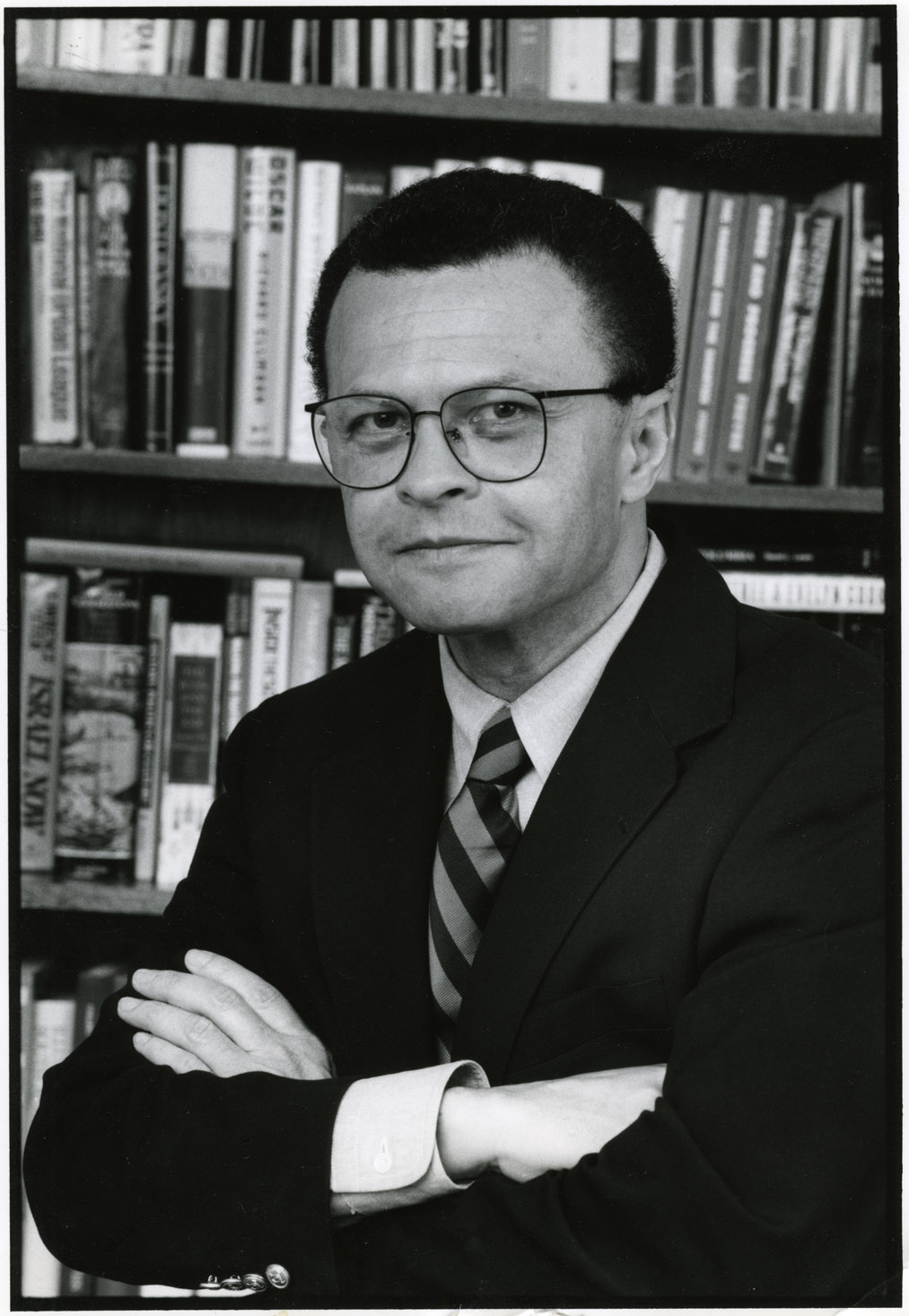

David Levering Lewis

Like W.E.B. Du Bois, the subject of his best-known work, David Levering Lewis went from a precocious childhood to a brilliant scholarly career. Lewis was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, on May 26, 1936, into a family devoted to education. His mother, Urnestine Bell-Lewis, a taught mathematics in high school, while his father, John Henry Lewis Sr., went from being a high school principal, to dean of the theological school at Wilberforce University, and then president of Morris Brown College. With this background, Lewis grew up in a family that he described as "like characters in a Jessie Fauset novel" and in a home frequented by the elite of African American society, from Adam Clayton Powell to Walter White, Marian Anderson, Thurgood Marshall, and Du Bois.

Speeding through high school in two years, Lewis entered Fisk University at the age of fifteen -- the same age as Du Bois when he entered Fisk -- and quickly distinguished himself in his major fields of history and philosophy, earning entry into Phi Beta Kappa. Although initially planning on a career in law, he changed course after a single semester at the University of Michigan, earning an MA in history from Columbia in 1959 followed by a PhD from the London School of Economics (1962). His dissertation was a study of liberal Catholic layman, Emmanuel Mounier, and his failed attempt to construct a "third force" in French politics that would transcend Socialism and Capitalism. The choice of subject matter, was rooted deeply in the integrationist and assimilationist ethos of his family, where the mastery of "the history that white Americans claimed as their own" was viewed as a mark of distinction.

After eighteen months of military service at an Army psychiatric facility in Landstuhl, Germany, Lewis began his academic career teaching medieval and Renaissance history at the University of Ghana. He found some of the brightest students of his career there and an environment that carried both conflict and promise, but after only one year, ideological differences among the faculty in Ghana led him to return to the United States and to appointments at Howard University (1965) and Morgan State (1966-1970). Convinced that the topic of his dissertation was already too stale to make for a suitable book, he switched focus to modern French history, but the future path of his career came unexpectedly. Early in 1968, the editors of Penguin's Great Leaders of the 20th Century series approached him with the prospect of writing a biography of Martin Luther King. Initially, he had doubts about the project, unconvinced that a biography of a man who was, after all, still young and evolving would succeed, but King's assassination changed all that. Based on extensive interviews with major figures in the civil rights struggle, his King: A Critical Biography (1970) was well received by historians, though not without controversy, and is considered one of the first books to take advantage of deep archival research in the King Papers, then at Boston University.

Despite the success of the King book and his growing awareness of the untapped potential in African American studies, Lewis returned to French history after taking a new position at Federal City College (later the University of the District of Columbia) in 1970. By the time his Prisoners of Honor: The Dreyfus Affair appeared in 1974, followed shortly by District of Columbia: A Bicentennial History (1976), Lewis surrendered to the lure and promise of African American studies. The result became a landmark. A conversation with his literary agent led to a fascinating exploration of the origins of the Harlem Renaissance and the self-conscious vanguard of African American intellectuals who sought to create an arts movement in service to the cause of civil rights. When Harlem Was in Vogue (1981) became an instant classic that.

This deep dive into African American history came at a challenging time in Lewis' career. After being fired from his position at the University of the District of Columbia, and pursuing a wrongful termination suit, he crossed the country twice for academic positions, joining the faculty at the University of California San Diego (1981-1985) and then at Rutgers, where he served as the Martin Luther King Jr. Professor of History until 2003. Unsurprisingly, given his record of accomplishment, these migrations had little impact on his scholarly productivity: in many ways, he entered the most important part of his career. Learning that the papers of W.E.B. Du Bois had recently been opened for research at the University of Massachusetts, Lewis became one of the first scholars to mine the collection deeply, intent on writing the first comprehensive biography of one the great minds of the twentieth century. Even while this new project was consuming his energies, Lewis somehow found time to spin out another noteworthy monograph: a study of European colonialism and African Resistance, The Race to Fashoda (1988).

But it was Lewis's writing on Du Bois that cemented his reputation, and particularly the monumental two-part biography, W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1919): Biography of a Race (1994) and W.E.B. Du Bois (1919-1963): The Fight for Equality and the American Century (2001). The first volume received both the Bancroft Prize and Francis Parkman Prize, while the second was awarded the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award. Even more notably, each volume was recognized with the Pulitzer Prize, making Lewis the first author to receive the prize for consecutive volumes on the same topic.

Lewis left Rutgers to become the Julius Silver University Professor and Professor of History at New York University in 2003. Since that time he has written two books: God's Crucible: Islam and the Making of Europe, 570-1215, which explored the relation between Islam and the West, and The Implausible Wendell Willkie: Leadership Ahead of Its Time (2011). Highly regarded in the profession, he has earned fellowships from the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, the National Humanities Center, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the American Academy in Berlin, the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, the American Philosophical Society, and the MacArthur Foundation. He was awarded the National Humanities Medal by Barack Obama in 2009 and the 2015 Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. Award for distinguished writing in American history of enduring public significance.

Lewis married twice. In 1966, he married Sharon Siskind, with whom he had three children: Allison, Jason, and Eric. After divorcing in 1988, Lewis met Ruth Ann Stewart, who at the time worked for the New York Public Library. The couple wed in 1994, and adopted a daughter, Allegra Stewart.