Background on Susan Kleckner

Greenham Commons

A pioneering filmmaker, artist, and activist, Susan Kleckner was a fixture in the art scene in New York City from the 1960s until the early 2000s. Largely self-taught as an artist, she worked across several media including photography, film, drawing, collage, installation, text, and performance, and she was a prolific diarist who recorded her life extensively in illustrated journals. As an active participant in the women's and peace movements, she made little distinction between politics, art, and life, and believed in using art to empower the voices of women and minorities and as a tool for peace and social progress.

Kleckner was born in New York City on July 5, 1941, one of four children of Anita (Roth) and Charles Kleckner. Following the death of her father in 1955 and her mother's hospitalization in the following year, Kleckner left home at the age of 16, supporting herself by working in stores and restaurants. In her early twenties, she took up photography seriously and despite limited formal education, drifted toward teaching as a profession. In the mid-1960s, she began working as a counselor for people with intellectual disabilities, combining her love for teaching and art later in the decade when she became the first female photography instructor at the Pratt Institute.

During the intensely creative year of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Kleckner's art, politics, and personal life were deeply interwoven. A staunch feminist, she was active with Women Artists in Revolution (WAR) and Feminists in the Arts, and she helped to found the Women's Interart Center (WIC), which supported women in the arts and trained women in technology and integrated arts practices. Her feminism provided a particularly powerful focus as she moved from still photography into filmmaking. Her first complete film was a 16-millimeter documentary made with in collaboration with Louva Irvine and Kate Millett in 1970. Often considered the first documentary about women produced by an all-woman crew, Three Lives depicted the daily struggles of three "ordinary" women, one who had fled a bad marriage for a new life in New York City, another a middle-aged chemist, and the third, a "nice Jewish girl" who had become a bisexual performance artist.

After Three Lives, Kleckner was invited to join another all-woman team to work on a documentary about the 1972 Democratic National Convention in Miami. As a counterbalance to the male-dominated coverage of American politics, the film, Another Look, highlighted major figures in the women's rights movement, including Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, and Bella Abzug, and centered on the presidential candidacy of Shirley Chisholm, the first African American and first woman to run for the Democratic Party's nomination for President.

Meanwhile, Kleckner embarked on her first self-directed film project, Birth Film, a provocative and intimate documentary about a live, at-home birth. From the time of its premier at the Whitney Museum in 1973, Birth Film was controversial: reviewers described audience members becoming sick due to the film's graphic nature. Hurt by this reception, Kleckner stepped away from filmmaking for several years, returning only in the 1970s with projects such as Pierre Film, Amazing Grace, Bag Lady, and Desert Piece.

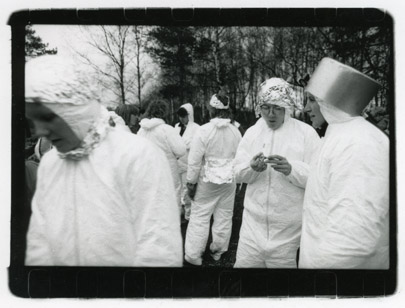

Steeped in a feminist commitment to the cause of peace, Klecker was drawn to the antinuclear weapons movement during the Reagan years. Between 1984 and 1987, she spent long stretches of time at the Greenham Common Women's Peace Camp in England, an encampment outside of a Royal Air Force base in Berkshire, England, where American cruise missiles were stored. During the years of the camp's operation, tens of thousands of people from around the world participated in demonstrations and civil disobedience to protest the missiles, repeatedly trespassing, blockading, and encircling the base, and decorating the off-limits fence. Although frequently evicted and arrested, the women maintained the encampment for nearly two decades, continuing even after removal of the missiles.

Inspired by Greenham, Kleckner returned to New York to organize what became one of her best-known works of performance art. Window Peace was a year-long performance in the storefront of SoHoZat, an underground magazine and comic book store, in which each week, a woman artist occupied a 5 by 6.5 foot display area furnished with a few basic amenities: a bed, portable toilet, television and tape deck, telephone, fridge, hot plate, and a curtain for privacy. During each "vigil," the women could do whatever they wished with the time and space, provided they remained in the window for the duration. For her own part, Kleckner spent her time editing footage collected from Greenham Common into a video entitled Greenham Tapes. While her journals reveal the stresses involved in organizing Window Peace, the project was highly acclaimed, receiving the Susan B. Anthony Award from the National Organization for Women in 1988.

Beyond her artwork and activism, Kleckner was admired for her teaching, particularly at the International Center for Photography (ICP) where she taught from 1982 to 2010. At ICP, she developed and taught courses such as New York at Night, Visual Diary, and Roll-a-Day, in which she impressed on her students the importance of personal identity and daily practice, key elements in her own work. In addition to teaching at ICP, Kleckner taught and led workshops at schools such as Pratt, NYU, and UMass Amherst.

Throughout her life, Kleckner struggled with mental illness, surviving several serious episodes of depression and hospitalization, which she documented in her art and writing. In the early 1980s, she became involved with Re-evaluation Counseling, a holistic, group-based approach to therapy and social change. Embracing the practice, she became an RC group leader and led co-counseling workshops that incorporated photography and other artistic practices in the healing process. Her role as a support leader took on an explicitly spiritual dimension after 2002, when she was ordained an interfaith minister by the New Seminary in New York.

In 2004, Kleckner learned that she had developed ovarian cancer, but she continued to teach, advise, and make art, and she even began to volunteer with SHARE, an organization devoted to supporting women with ovarian and breast cancers. After six years of struggle with her health, Susan Kleckner passed away on July 7, 2010, two days after her sixty-ninth birthday.