Background on Raymond Mungo

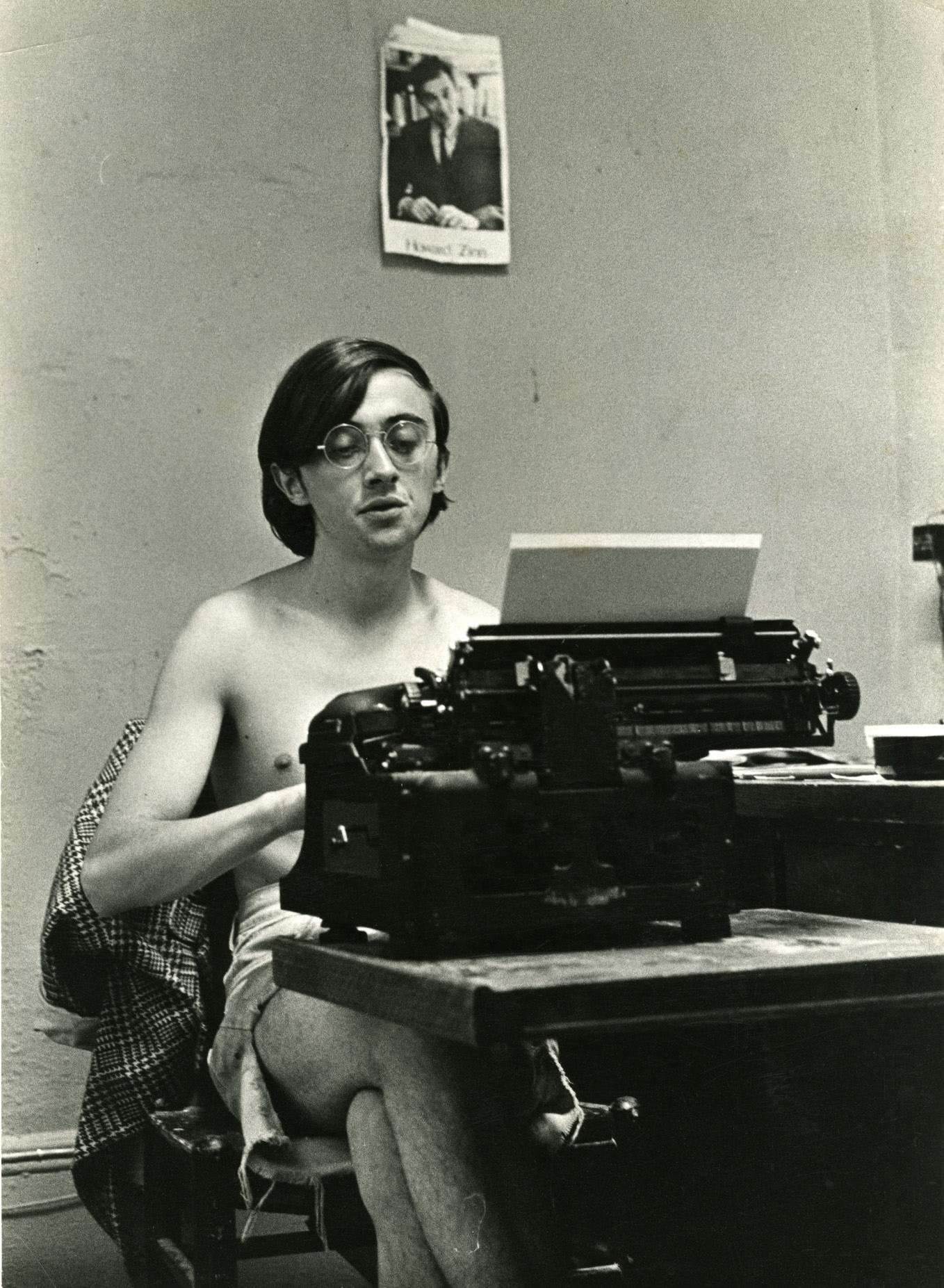

Raymond Mungo, 1967

Born in a "howling blizzard" in February 1946, Raymond Mungo became one of the most evocative writers of the 1960s counterculture. Through more than fifteen books and hundreds of articles, Mungo has brought a wry sense of humor and radical sensibility to explorations of the minds and experiences of the generation that came of age against a backdrop of the struggles for civil rights and economic justice, of student revolts, Black Power, resistance to war, and experimentation in communal living.

Raised in a working class family in Lawrence, Mass., and a product of Roman Catholic schools, Mungo emerged as a fully-fledged radical as an undergraduate at Boston University. From the time of his arrival in 1963, he was drawn headlong into the cultural and political ferment, seemingly a step ahead of his peers. A "violent Marxist" as a freshman, and a "friend of the working class," as he later wrote, he was introduced to drugs as a sophomore, and as a junior, he became a leader in the antiwar movement, working with East Coast Resistance to drive the ROTC from campus and traveling nationally to urge resistance to war.

It was as a writer, as much as an activist, that Mungo gained wide renown. As editor in chief of the Boston University News during his senior year, he became a constant irritant to the university administration, feeding the newspaper on a steady radical diet, and newspapers and writing soon took an even more prominent role in his life. Although initially intending to continue his studies at Harvard, thanks to a substantial fellowship, Mungo's connections with another young journalist and agitator, Marshall Bloom, led him down another path.

During the summer of 1967, Bloom was slated to become Executive Director of the U.S. Student Press Association, but after denouncing its parent organization, the National Student Association, for accepting funds from the CIA, he was voted down. In response, and "because we had nothing else to do," Bloom, Verandah Porche, and Mungo formed the Resistance Press Service, soon renamed the Liberation News Service (LNS), as a radical alternative to the Associated Press. Seeking to create links among anti-establishment presses and provide reliable news for the Movement, the LNS issued semi-weekly packets of hard news and opinion pieces, poetry, photographs, and artwork, covering liberation struggles at home and abroad and a variety of other events that were typically overlooked or distorted by the "straight" media. They were an instant success. From their offices in Washington, D.C., the LNS soon had over 800 subscribers, including many in the underground and college press.

When the LNS relocated to New York during the early summer of 1968, however, the simmering (though sometimes overstated) tensions between "politics" and "culture" in the organization came to a head, and by the end of the summer, Mungo wrote, "our glorious scheme of joining together the campus editors, the Communists, the Trots, the hippies, the astrology freaks, the pacifists, the SDS kids, the black militants, the Mexican-American liberation fighters, and all their respective journals was reduced to ashes" By August, the "Virtuous Caucus" led by Bloom and Mungo had split from the "vulgar Marxists" in New York and headed to communal lives in rural New England.

Worn out by the rancor and divisions, Mungo, Porche, and eight others traveled north to found a commune on 90 acres at Packer Corners, near Guilford, Vermont. In mid-August 1968, Bloom followed his associates northward, taking funds raised from a screening of the Beatles' Magical Mystery Tour to buy a farm in nearby Montague, Massachusetts, lugging the LNS printing press with him, and for over a year, the LNS factions in Montague and New York both produced news packets. The farms at Montague and Packer Corners -- Total Loss Farm -- were tightly connected from the outset, socially and politically, and both became centers for a remarkable number of writers and poets, artists and activists.

Within a year of arriving at Packer Corners, Mungo wrote two important memoirs about his experiences. Famous Long Ago: My Life and Hard Times with Liberation News Service (1970) was "a revealing parable of the split in the psyche of the new left between the fun-loving, fiercely individualistic life-stylers and the ideology-bound collectivists, and all that" according a review in the Village Voice. Appearing only a few months later, and nominated for the Pulitzer Prize, Total Loss Farm, which offered a year in the life look at the commune. Both were acclaimed and highly popular, and both have remained in print for decades.

Following the success of his first two books, Mungo left Total Loss Farm and by early 1970, he settled in California to continue writing, spending several years in San Francisco and Carmel before moving to Los Angeles. In a single year in Carmel, 1972, he completed the only screenplay of his career, Between Two Moons, a Technicolor Travelogue as well as his only novel, Tropical Detective Story: The Flower Children Meet the Voodoo Chiefs. His later books, mostly non-fiction, have covered a wide terrain, though all remain true to the essential countercultural values acquired in the 1960s. Among his books are San Francisco Confidential: tales of scandal and excess from the town that's seen everything (1995) and Palm Springs Babylon (1993), a satirical look at the corrupt lives of the film set; Cosmic Profit: How to Make Money Without Doing Time (1980) and No Credit Required (2004), a primer on "how to buy a house when you don't qualify for a mortgage"; Confessions from Left Field: A Baseball Pilgrimage (1983); and three books on becoming a writer. Mungo has also written two memoirs, Return to sender : or, When the fish in the water was thirsty (1975) and Beyond the Revolution: My Life and Times Since Famous Long Ago. In his own words, his literary output has sometimes been more successful, sometimes less, but he has "managed nonetheless a 30 year career in which he never held a 'real' job."

In 1997, Mungo completed a master's degree in counseling and became a social worker in Los Angeles, tending principally to AIDS patients and the severely mentally ill. He and his husband, Robert Yamaguchi, still live.