Background on Gordon Heath

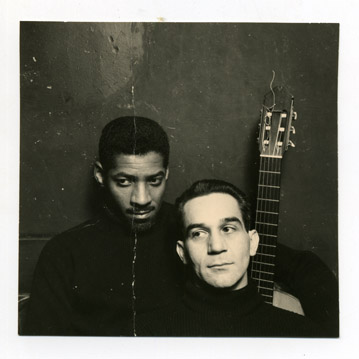

Gordon Heath (l.) and Lee Payant, Paris

A multi-talented performer, Seifield Gordon Heath was born in the San Juan Hill district of Manhattan on September 20, 1918.1 Heath and his half-sister Bernice were raised in a family of relatively recent immigrants: his mother, Harriette (Hattie), was a second generation American of African and Indian descent while his father Cyril Gordon Heath came originally from Barbados. As a steward for the Hudson River Night Line, Cyril had steady employment and in his later years, he was a devoted public servant, active in the local YMCA, neighborhood associations, and church-sponsored groups.

While studying at the Ethical Culture Society School in Manhattan and later at the Hampton Institute, Heath was drawn to the theater. As a child, he sang in St. Cyprian's Church choir and learned to play the violin and the viola with some skill, but the acclaim for his music was soon overshadowed by the attention he received on the stage. Winning a state-wide drama competition while still in high school, Heath began to get serious about acting, perhaps in reaction to his father's aspirations for music. In 1938, Gordon began to write and perform sketches for radio station WNYC and about the same time, he began training with a group of African American actors under the guidance of Marian Wallace. While in college at Hampton, he acted in several plays under the direction of his childhood friend Owen Dodson.

Heath landed his first Broadway role in 1943, playing the second lead in Lee Strasberg's South Pacific. Two years later, while working as a radio announcer, he was chosen for the lead in Elia Kazan's Deep Are the Roots, a provocative Broadway "race play." Playing the role of Brett Charles, an African American war hero who returns home to find that the "fight for democracy" in Europe had done little to change race relations in the Jim Crow South, Heath enjoyed a fourteen-month run in New York followed by five-months in London in 1947. In between, Heath made his directorial debut in the off-Broadway Family Portrait, in which he also played the lead. Widely acclaimed for his performances, Heath was soon lauded as "the next Paul Robeson."

Despite the success of Deep Are the Roots, Heath found that he and Brett Charles mirrored one another when it came to American race relations. After returning to the States from his time in London, Heath discovered the cold reality that racism limited his access to the types of roles he desired, and his nascent affection for Europe began to grow accordingly. Having met the man who would become his partner, an actor from Seattle named Leroy Payant, Heath left the U.S. in 1948 to try his luck in Britain. There, too, he was regularly passed over for coveted roles in favor of British actors, later remarking that in London, "each time, for each part... was a hustle."2

In search of "continuity in the theater," Heath relocated to the more congenial confines of Paris, where he and Payant established a nightclub called L'Abbaye. There, the two performed folksongs, spirituals, and the blues in an intimate setting, and soon discovered that their original aim of providing a living between acting gigs was selling themselves short. L'Abbaye quickly caught on in Paris, appealing especially to the community of expatriates and artists, and it remained a popular for 27 years.

From his base in Paris, Heath and Payant translated the popularity they enjoyed at L'Abbaye into at least three record albums and several tours through Europe and the Middle East. His efforts to build his career as an actor, however, proved somewhat less successful. He appeared fairly often on radio and television in Europe and took roles -- mostly supporting roles -- in films including Sapphire (1959), the Nun's Story (1959), and The Madwoman of Chaillot (1969) while doing narration for the animated Animal Farm (1954) and other productions. On stage, whether in England, France, or the United States, Heath continued to find it difficult to achieve the artistic freedom and types of roles that he desired. As Helen Gary Bishop explained:

The French were only casting him black roles and, in their nationalistic zeal, would not give an American, however talented, a directing job - certainly not in any subsidized theater. There were even quotas on the number of American and English plays, which could be done in the commercial theater. And in England it appeared that he was being typecast as a West Indian.3

In the 1960s, Heath attempted to circumvent the racism he faced by founding the Studio Theater of Paris (STP), an English-speaking theatrical workshop and troupe comprised largely of expatriates from England and the U.S. During its ten years of operation, Heath's led the STP performers in such plays as the Glass Menagerie, After the Fall, The Skin of Our Teeth, In White America, The Slave and the Toilet, and Kennedy's Children. Heath served not only as director, but as an all-purpose impresario, creating the playbills and posters, working publicity, and booking venues for the performances through the American Church of Paris and other locations. STP also served as a forum for lectures from visiting professors and critics, and for round table discussions, and they sponsored Martin Luther King, who preached at the American Church during one of his visits. Although never defined solely by their racially- and politically-conscious productions, nor by the charge that they performed "art for politics sake," the STP lost much of its vigor after the progressive leader of the American Church was replaced by a more moderate successor.

In the 1970s, Heath began performing more frequently in the United States. He returned home for five months in 1970 to play the lead in Oedipus at the Roundabout Theater, and later that year he and Payant performed Dr. Faustus in Washington D.C. The changes affecting the American theater, and Black theater in particular, left him with mixed emotions. "Black theater was a reality," he noted, "off and off-off Broadway were healthy, and government subsidies and funding seemed abundant."4 At the same time, he feared that the younger generation of Black actors were rejecting their social past, the political past, and the theatrical past. Still, the turbulence of the time and the positive changes affected him deeply: "The fact of Negroes playing with public approbation, a general public...," he wrote, "playing these parts we never thought we'd get a crack at (such as Lear) is so exciting I can't tell you."5

Although a generation older than most of the artists associated with the Black Arts Movement, Heath developed a working relationship with artists such as the director Woodie King and writer A.B. Spellman. After Payant's death in 1976 and the subsequent shuttering of L'Abbaye, Heath appeared more regularly in the U.S., and even temporarily settled in New York, leavening his acting with politics by organizing a community group and a leading rent strike to improve conditions in the building in which he had grown up. Although he returned to Paris to live, he continued to perform on both sides of the Atlantic for the rest of his career. His final performance, a production of Wole Soyinka's The Lion and the Jewel done in conjunction with the choreographer Pearl Primus, with whom Heath had worked forty years earlier, was staged at the University of Massachusetts in 1987.

The memoir that Heath was writing at the time of his death on August 31, 1991, was published by the UMass Press in 1992 as Deep Are The Roots: Memoirs of a Black Expatriate.

Footnotes

- As Heath reports in his memoirs, his "father and his genteel cohorts" had had the district renamed "Columbus Hill" during Gordon's youth. Gordon Heath, Deep Are the Roots: the Memoirs of a Black Expatriate (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1992) p.11.

- Encore American & Worldwide News, April 5, 1976.

- Helen Gary Bishop, "Gordon Heath - American Actor Between Two Continents," The Soho Weekly News, April 21, 1977.

- Ibid.

- "The Two Worlds of Gordon Heath," Encore American & Worldwide News, April 5, 1976.