Background on Frederick L. H. Willis

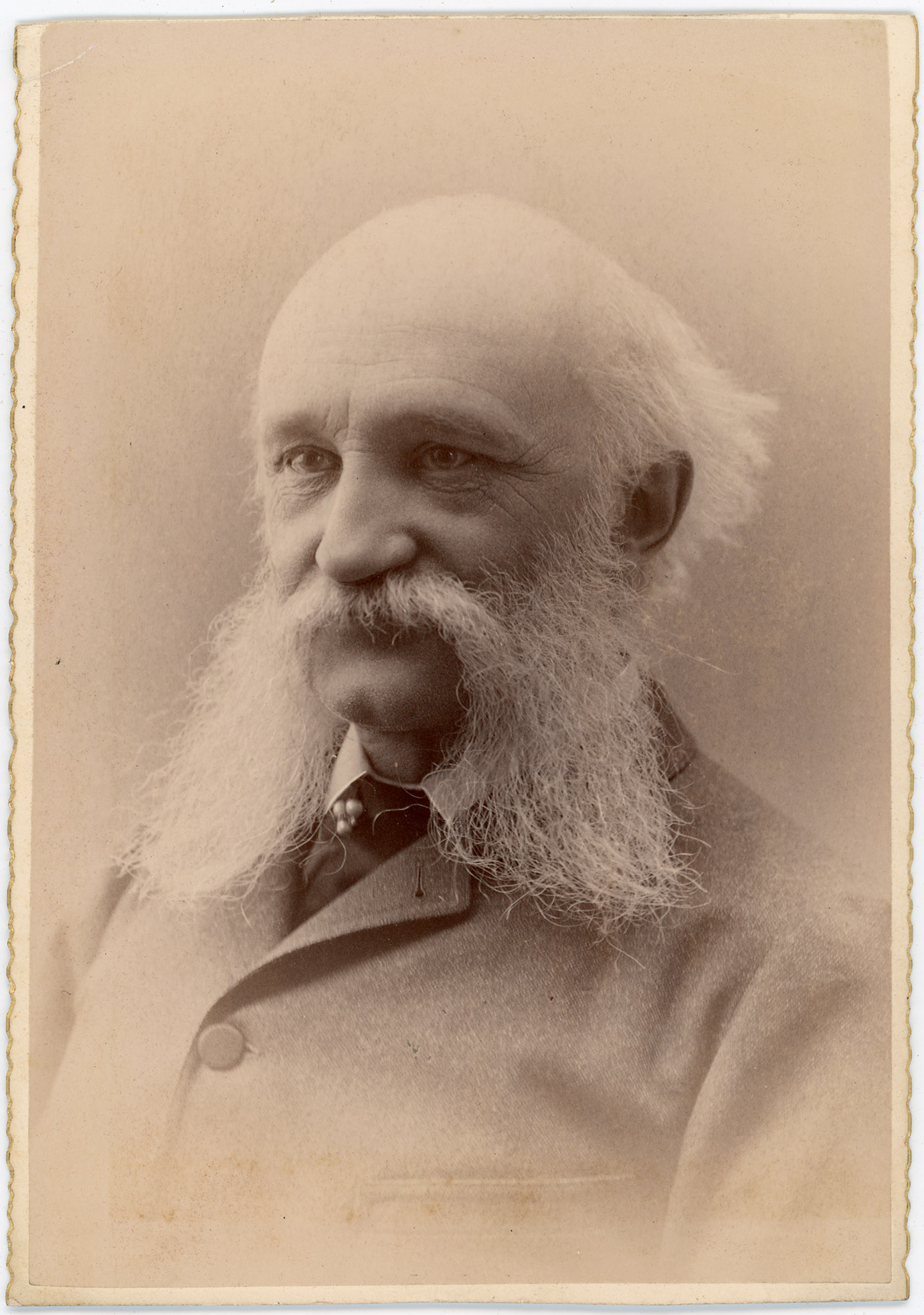

F. L. H. Willis, ca.1887

In 1857, Frederick L. H. Willis earned the singular distinction of being expelled from Harvard Divinity School for acting as a spirit medium. In a life marked by misfortune, he carved out a unique public role for himself as an ardent proponent of Spiritualism, a lecturer and preacher, homeopathic physician, and writer.

Born on January 29, 1830, Willis was the only child of Lorenzo Dow Willis, a merchant from Cambridge, Mass., who could boast of solid social connections and a rising place in the world. All that would change. The family's taste of prosperity ended suddenly when Lorenzo's business partner absconded with their company's fund, and even though Lorenzo won release from debtor's prison, the family's fortunes darkened further when Lorenzo's wife, Eleanor (Hovey), died three days after giving birth.

After four years of struggle with financial and emotional distress and failing health, Lorenzo called upon his wealthy in-laws to raise his son. Under their care, Fred received an education in the Cambridge public schools and he reportedly apprenticed with an apothecary. Yet from early in life, he found little intellectual kinship in his adoptive home. Willis's grandfather Hovey, an archconservative, was a founder of the Baptist Church in Cambridge and brought a stern edge to both his religion and life. Willis rebelled. After initially acceding to the faith, Willis soon developed a loathing for the Church, and by the age of twelve, he was said to have been expelled as a heretic for rejecting predestination. At thirteen, he was expelled from his grandparent's home.

Thrown out into the world, Willis experienced another surprising turn of fate. While traveling by stagecoach during the summer of 1844, hoping to spend a summer in the country with a relative, a kind woman helped care for him after he wounded his hand in the stage door. Abba May Alcott -- wife of Bronson Alcott -- took an immediate liking to the young man, and within a week, Willis earned an invitation to visit, which soon became a long-term arrangement. Off and on for ten or twelve years, he lived with the Alcotts, becoming a close companion of the daughters, Louisa May, Abigail, Elizabeth, and Anna. It was under their roof, that he met some of the great intellectual figures of the day, including Emerson, Thoreau, and Hawthorne, and he prepared there for Harvard Divinity School under the care of the eminent divine, Thomas Starr King. Willis explicitly denied claims in contemporary newspapers that he was the model for the character Laurie in Louisa's Little Women, but his intimate connections with the family ran deep.

As a student at Harvard during the fall of 1855, Willis experienced a series of profound visions, trances, and spirit manifestations that confirmed his gifts as a powerful Spiritualist medium. The phenomena he exhibited were remarkable, including raps and spirit voices, mental telepathy and apports, levitation, and accordion serenades by spirit musicians. Although reportedly reluctant to take part in public displays, he was persuaded by a woman acquaintance to try to convince a skeptical Harvard faculty member, Henry L. Eustis, of the veracity of spiritual claims. Willis's decision proved to be his undoing. While responding to mental questions during a dark seance with Eustis, the professor grabbed Willis under the table and denounced him on the spot as an impostor. According to Spiritualist writer and medium, Emma Hardinge Britten, it became clear that Eustis, the woman who encouraged Willis, and the members of the circle had all made "preconcerted arrangements" to trap the young student. Despite receiving letters attesting to his honesty from Thomas Wentworth Higginson and others, Willis was suspended from Harvard in April 1857 on the grounds of "imposture." The Willis case fed directly into a trial of Spiritualist mediums held at Harvard later that year, adjudicated by Professors Louis Agassiz, Benjamin Pierce, Eben Horsford, and N. B. Gould.

Although he failed to complete his degree, Willis landed a pulpit in relatively short order, accepted an offer from a fellow Spiritualist, Henry C. Gilbert, to settle in Coldwater, Michigan. For a time, he lived in the Gilbert home. On October 8, 1858, Willis married Love Maria Whitcomb of Hancock, N.H. -- daughter of Love Foster Whitcomb (1789-1873) and Henry Whitcomb (1787-1831). An aspiring writer, Love had overcome a protracted illness as a young woman through a mesmeric healer, and by the mid-1850s, she was herself displaying mediumistic skills. While tending to the small congregation in Coldwater, both Willis and his wife were contributors to Spiritualist publications such as Tiffany's Monthly and The Banner of Light, writing on Spiritualism, healing, and reform, and they published in the mainstream press as well. Spiritualism connected their whole family. Love's mother took up the cause despite having no mediumistic talent of her own, and her mother's cousin, Sarah Bartlett, married a major Spiritualist writer, Allen Putnam.

Preaching in Coldwater was a constant challenge for Willis. His Society there was small, but avid, but he expanded his base by speaking in towns as far away as Toledo, Ohio, and he branched out to give public lectures and courses on men of modern theology and other topics. The audiences for these inspired lectures, he reported, were often large and enthusiastic, and Coldwater played host to major figures in the Spiritualist world such as Emma Hardinge Britten (a medium and writer) and the Davenport Brothers (stage performers). But for all the successes, Coldwater proved to be less than inviting for a preacher with liberal sentiments. A deep-seated and sometimes bitter animosity toward Spiritualists within the community affected him deeply, compounded during the winter of 1860-1861, by a falling out with the Gilbert family over the "intolerable" behavior of Gilbert's new wife.

During the spring or summer of 1863, the tensions grew to such a degree that Willis decided to leave Coldwater and change course in life. Taking a degree from the New York Homeopathic Medical College in 1865, he accepted a position as Professor of Materia Medica at the Women's Medical College, and by the late 1860s, he went about building a practice in Boston, Willimantic, Conn., and Rochester, New York. Despite his unpromising start in Michigan, he gradually built a successful practice that won him a degree of financial stability. In 1868, he purchased a property that would become his family's seat for the better part of a hundred years. Situated on the west shore of Seneca Lake, his estate, Glen Eden, started as a summer home in 1874 and remained in family hands for a century.

Toward the end of his life, Willis maintained that he practiced two professions, medicine and preaching. While tending to patients, he continued to preach, usually from the Unitarian pulpit, and lectured and published regularly on religion, history, the occult sciences, healing, and other topics influenced by his Spiritualist faith and heterodox inclinations. He reached a culmination of sorts when he was asked to delivered a speech at the Fiftieth Anniversary celebration of the Spiritualist movement in 1898, "Can Spiritualism claim to be a religion?" Love Willis died at home in 1908, followed by Fred's death to "myocardial insufficiency" on April 12, 1914. They are buried together in the Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, N.Y.

The Willises had two children. The first, a daughter, died at the age of fourteen months, while the second, Edith Lenora Willis (b. 1865), became a prolific poet and writer who helped to co-edit and complete her father's memoir of the Alcott family (1915). In 1886, Edith married Dr. Samuel H. Linn, a Civil War Navy veteran who served for many years as the official dentist to the court of Czar Nicholas II of Russia. The Linns had two sons, Willis (who married Ethel G. Hamilton) and Benjamin F. Linn. After Samuel's death in 1916, Edith married a second time to George Mather Forbes, a member of the faculty at the University of Rochester.