Background on Esperanto Information Center

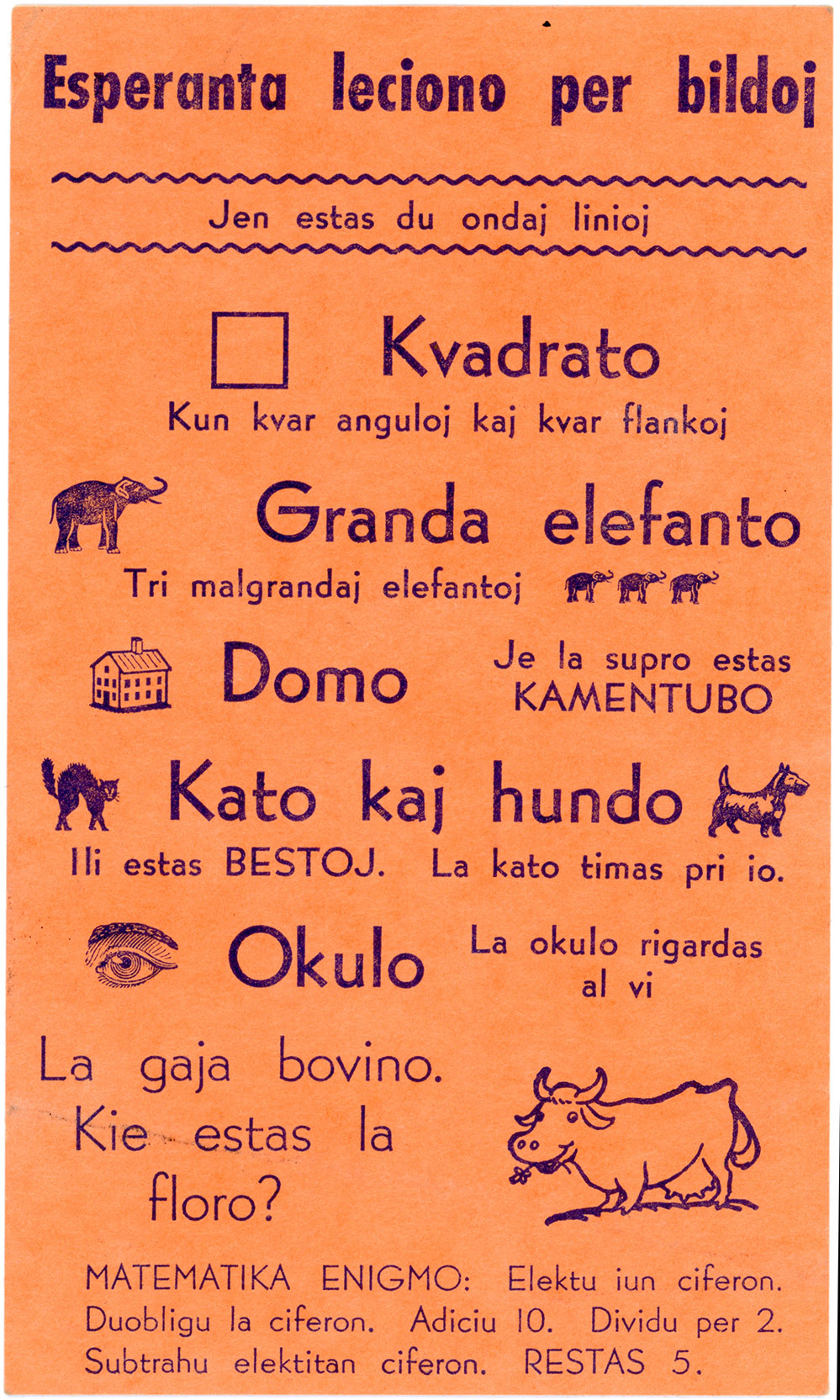

Esperanta leciono per bildoj, ca.1968

The labor educator Mark Starr first became interested in Esperanto while serving time in prison in his native England. Born into poverty in Shoscombe, Somerset, in 1894, Starr left school at 13 to earn his keep, and was soon drawn into the labor movement. Working as a builder's mortar boy for a year, he entered the local coalmines and then relocated to the thicker coal seams of South Wales, where the the simple country Methodism of his youth quickened into Socialism.

Starr's life hit a watershed in 1913 when an essay he wrote on the Osborne Judgment earned him a Rhondda Miners' Scholarship to restart his formal education at the Central Labour College in London. With war looming, however, and the likelihood that students and staff alike would be called to service, the College was barely viable, and nearly on his own, Starr pressed on with his studies. Registering as a conscientious objector at the outbreak of the war, he was permitted to return to the mines (deemed essential to the war effort), but by 1917, standing out of the conflict became untenable. Not budging on his convictions, Starr was arrested and sentenced to prison. It while incarcerated at Wormwood Scrubs that an Esperanto translation of the New Testament sparked his zeal for the ideals of universal language. For the next six decades, he devoted himself to promoting this constructed language as a tool for promoting international dialog, intercultural understanding, and world peace.

Completing coursework at the Labour College after release from prison, Starr delved into the "Plebs" self-education movement, a natural fit for someone of his background, and helped to found the National Council of Labour Colleges (NCLC) in 1921. In this role as an educator, he became a prolific propagandist, mixing advocacy for the labor cause with keen historical and economic analysis. Among his numerous books and pamphlets were: A worker looks at history (1917), A worker looks at economics (1925), Trade unionism, past and future (1923), Lies and hate in education (1928), Workers' education in the United States (1941), Labor and the American Way (1952), and Creeping Socialism vs. limping Capitalism (1954).

A brief commitment to Communism ended for Starr when he saw the Soviet system firsthand during an Esperanto Congress in Leningrad, after which he settled gradually into a pragmatic Socialist-inflected liberalism. Aspiring to office, he stood unsuccessfully for Parliament on the Labour Party ticket in 1924, but tensions over the direction of British labor helped spur his decision to immigrate to the United States in 1928. A position at the Brookwood Labor College in Katonah, N.Y., lasted until that institution began to founder during the middle years of the Great Depression, after which Starr landed as educational director for the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. As in England, he mixed educational work with forays into formal politics, aligning with the American Labor Party and the Liberal Party of New York, and running (unsuccessfully) as the Liberal Party candidate for the Fourth District in Queens in 1946.

For Starr, Esperantism was always a congenial partner for Socialism. He had taught courses in the language during his time with the NCLC and was active in Esperanto organizations as early as the 1920s. After retiring from the ILGWU in 1960, he joined the Esperanto Information Center, serving as its chair from 1965 to 1972. Located at 156 Fifth Ave. in New York City -- the "unfashionable end" of the street, according to the 1969 EIC Report -- the Center was one of two information "agencies" of the Esperanto League for North America, the other located in the Bay Area of California. Established by Bernard Stollman in 1962, the EIC was a clearinghouse for information about the movement and a connector of people and publications, sharing information about the language to "anyone who consults the telephone book and the 'yellow pages of the classified.'" Starr and his associates fielded queries from committed Esperantists, aspiring learners, the media, and the curious public, and they worked to raise awareness and interest in the language with publishers, writers, students, educators, and political figures. Working with the Esperanto Book Center, their co-tenants on Fifth Avenue, the EIC produced and distributed publications in and about the language. During Starr's tenure in the late 1960s, in particular, the EIC was a meeting place for Esperantists and a connector of groups ranging from international organizations to local and regional clubs and the United Nations.

Starr retired from his duties at the EIC in 1974, aged 80, and died on April 14, 1985.