Background on Otis A. Hood

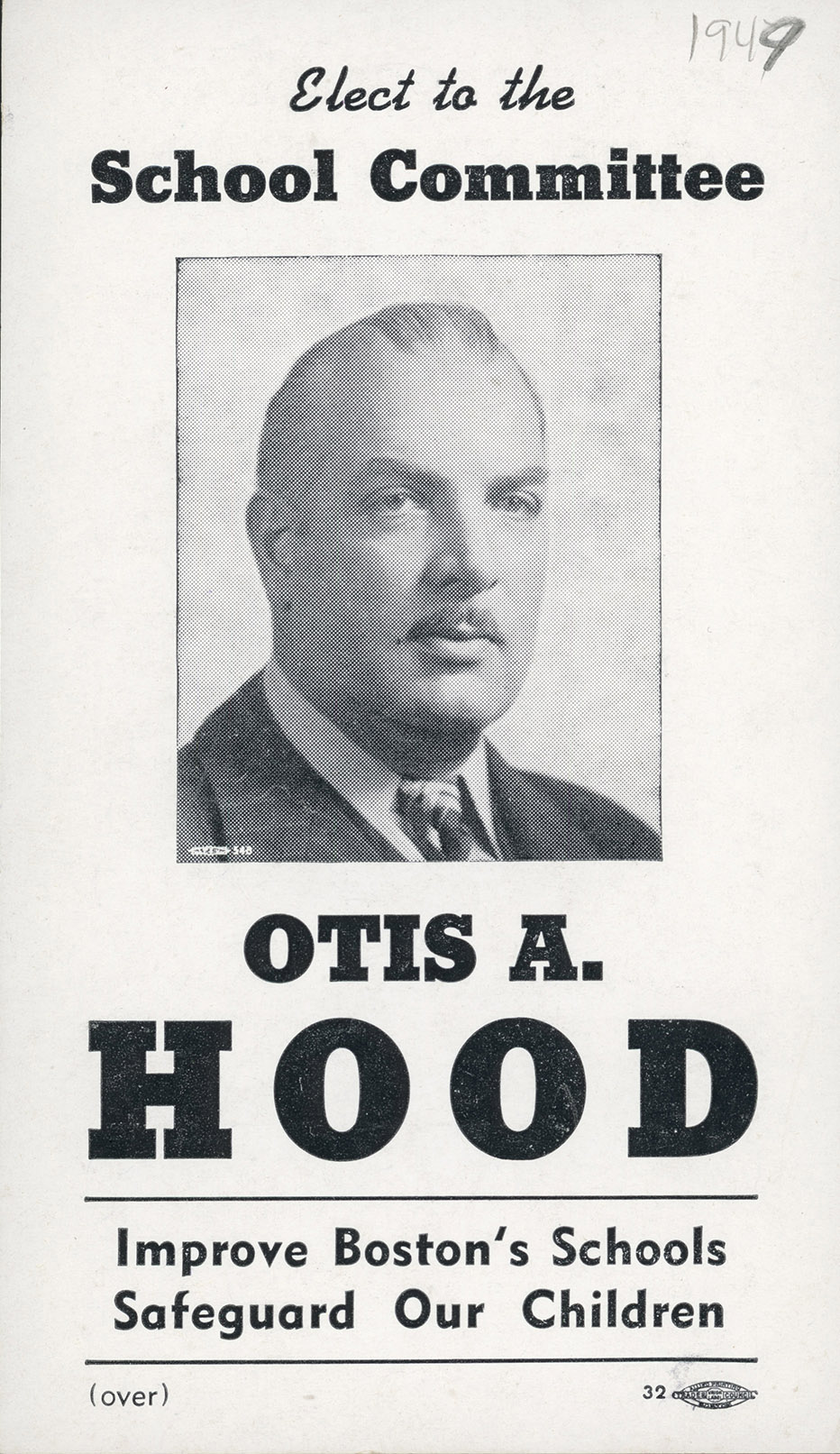

Otis Hood for School Board, 1949

An architectural sculptor and chair of the Massachusetts Communist Party during the height of McCarthy-era repression, Otis Archer Hood was a child of the working class. Born in either North Abington or Randolph, Massachusetts (depending on the source), on March 29, 1900, Hood was a descendent of old Yankee stock, but not a member of the economic elite. His father, Otis R. Hood, worked as a rough rounder and stitcher in a shoe factory, and his siblings worked either in the shoe factories or, for his sisters, as stenographers.

Raised without a strong political compass, Hood moved to Boston as a young man and worked in the Boston Public Schools teaching clay modeling and as an architectural modeler. The Depression of 1929, however, profoundly changed his course in life. Unemployed for the first time in his life, he encountered a group of radicals who introduced him to the Communist Manifesto, and soon thereafter to join the Communist Party formally in 1934.

After organizing for the Party in Vermont for a brief period, Hood returned to Boston and rose through party ranks. He married a fellow Communist, Frances Briggs Allen, in 1939 (a party member since 1936) settling in a rental in the Fenway prior to the war and in half a duplex in Roxbury after. Unlike other Party members, Hood never hid his political commitments. As chair of the state Communist Party for many years, he became a perpetual -- perpetually unsuccessful -- candidate for public office, beginning with a campaign for Mayor of Boston in 1937, four runs for governor (1938-1944), four attempts the for Boston School Board (1943-1949), and at least one for representative in the Massachusetts General Court (1952). His best showing was for School Board in 1945, when he received over 27,000 votes.

In addition to running for office, Hood frequently represented Communist ideas at public forms and through radio broadcasts, always insisting that the state's suppression of political ideas was unconstitutional. He became well known as an advocate for unemployment insurance, rent control, and public transport, and he was a prominent voice opposing antisemitism and racism. The state did not ignore him. During the post-war repression of Communists, he refused to answer questions before the state commission on subversive activities, earning arrest in 1954 for violating the 1951 law banning the Communist Party. Although the case against him was quashed in 1956, he was among five Communists (including Sidney Lipshires and Michael Russo) indicted under the Smith Act in June 1957 on charges of conspiracy to overthrow the U.S. government. These charges too were dismissed on the grounds that there was insufficient evidence that the defendants had attempted to incite the overthrow of the government.

Out of the public eye for most of the last two decades of his life, Hood died in Randolph, Mass., on Nov. 11, 1983, leaving behind his wife and two daughters. His body was donated to the Boston University Medical School.