Background on Theodore W. Allen

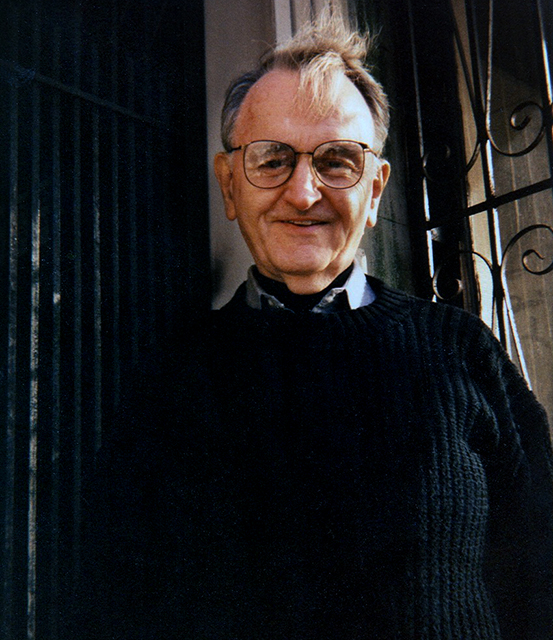

Ted Allen

By Jeffrey Perry, with additions by Susan Creighton.

Theodore W. "Ted" Allen (1919-2005) was an anti-white supremacist, working class intellectual, and activist who researched and wrote outside of the academic community for almost seventy years. He developed his pioneering class struggle-based analysis of "white skin privilege" beginning in the mid-1960s; authored the seminal two-volume "The Invention of the White Race" in the 1990s; and in his writings and speaking consistently maintained that the struggle against white supremacy was central to efforts at radical social change in the United States.

Born in Indianapolis, Indiana, Allen grew up in Paintsville, Kentucky and Huntington, West Virginia where he was "proletarianized" by the Great Depression. He joined the American Federation of Musicians, worked in the coalmines, served as a United Mine Workers Union Local President, and joined the Communist Party. After hurting his back in the mines, he moved to New York City and lived his last fifty years in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn. During those years, he taught at the Jefferson School of Social Science, did research with the Labor Research Association, and worked various jobs including factory work, teaching, the post office, and the Brooklyn Public Library. In the 1940s, he wrote probing analyses of conditions and struggles in the coal mining industry. In the 1950s, he wrote on radical political economy and produced critical analyses of U.S. capitalism, U.S. imperialism, and the Communist Party USA's analysis and program (which he thought was not radical enough), sometimes writing under the pseudonyms "Molly Pitcher" or "Milton Palmer."

In the 1960s, after breaking from the Communist Party, Allen set out on his own independent research course. He sought to address the question of "Why No Socialism in the United States?" and how to explain the relative lack of class-consciousness by U.S. workers as compared to workers in other capitalist countries (what was referred to as "American Exceptionalism"). Inspired by Black Reconstruction by W. E. B. Du Bois, he analyzed and wrote about the "white blindspot" and "white skin privilege" (in such articles as "White Blindspot" and "Can White Workers Radicals be Radicalized") and began forty years of work that focused on white supremacism as the principal retardant of class consciousness among European-American workers and on the importance of the left and working class and progressive movements struggling against white supremacy. Noel Ignatiev was a close collaborator during this time period, and the two of them corresponded frequently as well as reviewing each other's work and co-authoring articles.

In the early 1970s, while involving in many of the debates of the New Left, he began twenty-plus years of research in Virginia's colonial records and in probing analysis of Irish history as he developed an analysis that racial oppression was a form of ruling class social control not determined by phenotype or skin color. This research resulted first in the unpublished The Kernel and Meaning (drafts written between 1969 and 1976) that dealt with the development of white skin privilege, its relationship to land acquisition and use, and problems with U.S. historiography.

Next followed drafts of the unpublished book Peculiar Seed: The Plantation of Bondage (drafts written circa 1976) that addressed the subject of class struggle and the origin of racial slavery in continental Anglo-America.

Written between 1985 and 1997, Allen's exhaustively researched The Invention of the White Race was published in two volumes in 1994 (Vol. 1) and 1997 (Vol. 2), and republished in a two volume set in 2012. With its focus on racial oppression and social control, The Invention of the White Race is one of the twentieth-century's major contributions to historical understanding. Allen's major thesis -- that the "white race" was invented as a ruling class social control formation in response to labor solidarity as manifested in the latter (civil war) stages of Bacon's Rebellion (1676-77) was reinforced by two important corollaries: 1) that the ruling elite deliberately instituted a system of racial privileges to define and maintain the "white race" and to implement a system of racial oppression, and 2) that the consequence was not only ruinous to the interest of African Americans, it was also disastrous for European-American workers. In developing these theses Allen challenges the two main ideological props of white supremacy -- the notion that "racism" is innate, and it is therefore useless to struggle against it, and the argument that European-American workers benefit from "white race" privileges and that it is in their interest not to oppose them and not to oppose white supremacy.

Over his last thirty years, Allen wrote hundreds of published and unpublished articles and letters challenging white supremacy, capitalist rule, sexism, and U.S. Imperialism as well as numerous poems. In his last few years, he wrote an important philosophical piece "On the Individual and the Collective" and a major unpublished work, "Toward a Revolution in Labor History" (drafts written between 2002 and 2004).

Ted passed away early in 2005 from deteriorating health issues. His friends and colleagues hosted memorial services for him both in his home city of New York, and in Virginia near the site of Bacon's Rebellion.

Particularly significant in Allen's work is the full-scale challenge it presents to what he refers to as "The Great White Assumption" -- the unquestioning acceptance of the "white race" and "white" identity as skin color-based and natural attributes rather than as social and political constructions. His thesis on the origin, nature, and maintenance of the "white race" and his understanding that slavery in the Anglo-American plantation colonies was capitalist and enslaved Black laborers were proletarians, contains the basis of a radical approach to United States labor history.